In the decade of 1930, automobiles promised a new measure of mobility for the American middle class, however, in the age of segregation, the road was anything but open to African-American motorists. Finding a mechanic, restaurant or hotel on a long car trip can be difficult or even dangerous.

Growing up in Baltimore in the 1950, author and playwright Calvin Alexander Ramsey never really questioned why his family, like every other African-American family that knew, he would go on vacation by car at 2 or 3 in the morning.

According to him, he also did not think about the fact that his family always slept in private homes instead of hotels, used the side of the road as a bathroom and packed his own food for the duration of the trip.

Only years later, Ramsey realized that his His parents avoided restaurants, gas stations, and hotels to protect him from racist demeaning and the very real dangers of traveling as a black man in the 1936 in United States.

Until that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 formally ended segregation and criminalized discrimination on the basis of color, the tradition of the “great American road trip” was very different for African-American families.

Black motorists traveling outside major city centers had no way of knowing if the local gas station would sell them gas or if there was a restaurant serving African-American customers within a radius from 100 miles.

The man behind the “Green Book”

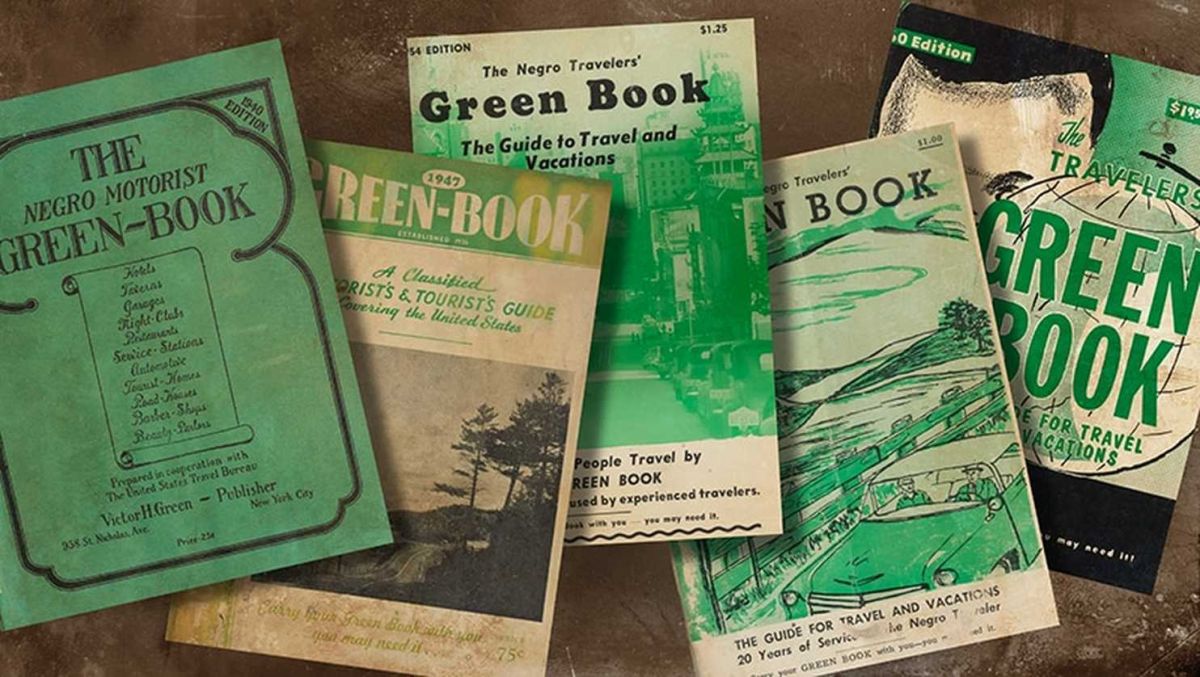

On 1936, a black mail carrier living in Harlem, New York, decided to do something about it. Inspired by Jewish publications that listed safe places for Jewish travelers to eat and sleep on the road, Victor Hugo Green published the first edition of “The Black Motorist’s Green Book.”

Within the pages of the “Green Book “, as it became known, black travelers could find state-by-state listings of hotels and private “tourist houses” for the night, and restaurants, barbershops, gas stations, and stores where they were welcome.

Ramsey, who wrote a popular children’s book in 1956 called “ Ruth and the Green Book,” as well as a play on the “Green Book,” explains that Green relied on a network of African-American letter carriers across the country to compile listings of businesses and private residences, then mailed the addresses. mail to his wife in Harlem, who would add them to the ever-expanding publication.

A new edition of the Green Book has been published every year since 1940 to 1964 and was sold at black-owned Esso service stations.

The “Green Book” was a lifeline for black travelers, many of whom brought back fresh memories of humiliation at the hands of the racist white business owners, and that it is worth mentioning that many northern and western towns and cities had “sunset laws” that stated that no black person could travel within the city limits after dark.

The Green Book: guarantee of non-degradation

The “Green Book” was created to ensure that other black families do not t had to endure such painful degradation at a time when many racist business owners felt it was perfectly acceptable to turn away black customers.

Browsing through the edition of 1940, there are paid advertisements for businesses that were owned by African-Americans, in addition to detailed listings from every major city in every state.

In some places, the options were limited. South Dakota, for example, had only two listings, a gas station and Mrs. J. Moxley’s private tourist home in 915 N. Main.

Victor Green may have only had an eighth grade education, but he used his intelligence and leadership skills to create a publication that opened America’s highways and highways to millions of black families.

Green died in 1936 , four years before the passage of the Civil Rights Act, a moment I had long awaited.

Also read:

· Louisiana “pardons” African-American activist who challenged racist laws in 1892

· Statue made by a Puerto Rican sculptor will be the first of its kind black woman in US Capitol

· What is “climate racism” and how it impacts the United States