The Biden administration and congressional Democrats have expressed a strong desire to correct systemic racism and structural inequities in our health care system, and have spent a substantial amount of both time and money on this issue.

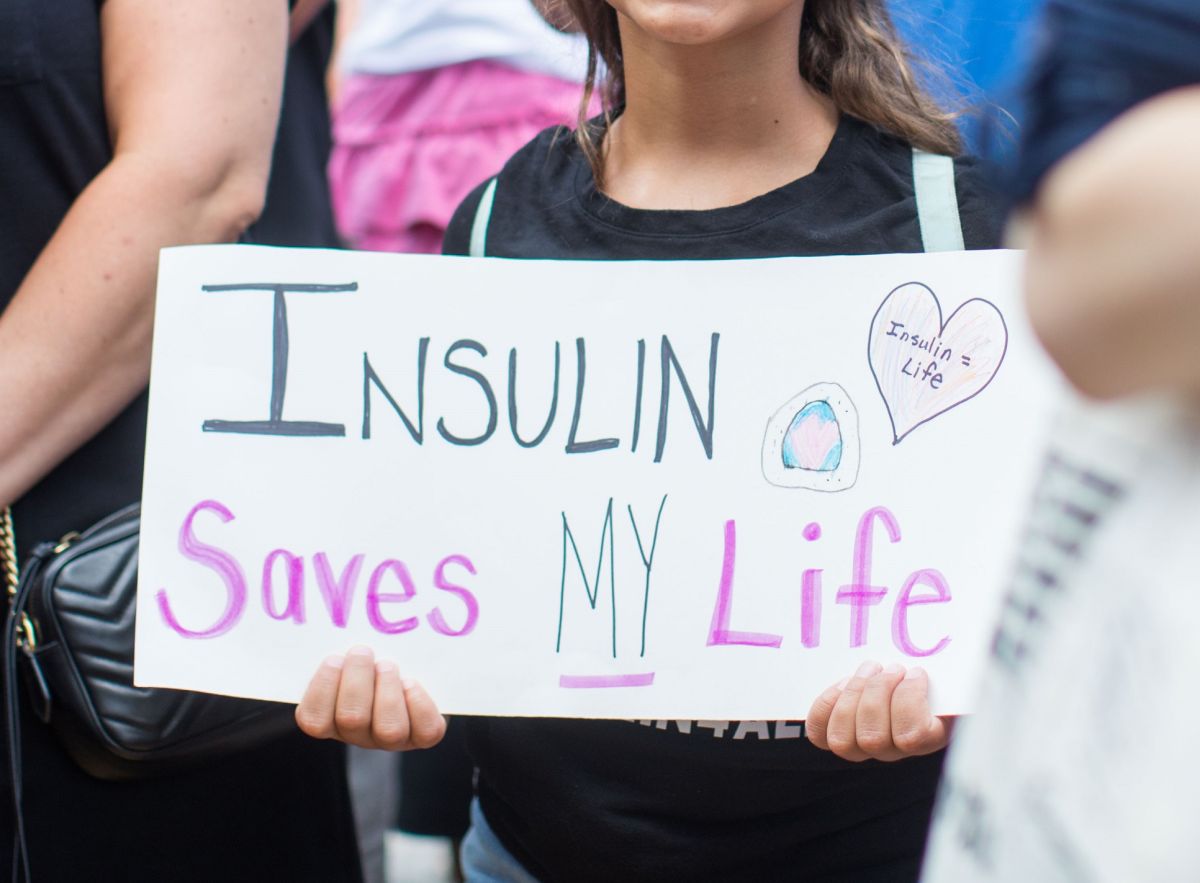

Last year’s Inflation Reduction Act, in particular, introduced a long list of reforms to improve health equity. The Act limits out-of-pocket drug spending for Medicare enrollees to $2,000 per year, limits the out-of-pocket cost of insulin, the standard treatment for diabetes, which disproportionately affects African-American and Hispanic Americans, to $35 per year. month and extends subsidies to help people pay for health insurance plans. These reforms benefit everyone, but especially underserved communities, which have always had less access to quality, affordable care.

But there is no perfect law, and the IRA Act would benefit from a minor adjustment designed to encourage research into life-saving “small molecule” drugs, which are particularly needed in underserved communities.

Ironically, the law intended to combat inequality contains a provision that demands discriminatory treatment, although fortunately, the discrimination is directed at different types of drugs, rather than at people.

By contrast, Medicare officials can negotiate lower prices on small-molecule drugs, which often come in pill or tablet form, and start saving after those drugs have been on the market for 9 years.

That disparity gives drugmakers an incentive to devote more resources to biologics rather than small-molecule compounds, because the longer exemption period for biologics offers the potential for higher profits.

It makes no medical or fiscal sense for the government to tip the balance in favor of biologics at the expense of small molecule treatments. Both types of drugs save lives. And small molecule drugs actually offer several unique advantages.

Because small molecule drugs usually come in pill form, patients get them at a pharmacy or by mail order, and can take them at home, which can be more convenient than biologics (such as chemotherapy infusion ) that generally require administration under medical supervision in a medical facility.

Racial and ethnic minorities often have far worse access to medical facilities and the transportation services necessary to reach them than do more affluent communities.

For example, Hispanic and African American people are disproportionately more likely than white people to rely on public transportation in urban areas. Public transportation systems are still racially stratified, with underserved communities receiving subpar service. African-Americans and Hispanics have to wait longer for bus service, and the buses do not serve as many stops.

In other words, minority patients are more likely to have difficulty accessing biologics, compared to small-molecule pills that can be shipped to their homes or picked up at a local pharmacy. So it would be concerning if drug developers moved away from small molecules and toward biologics.

Fortunately, a solution to this particular problem is relatively simple. Congress could amend the Act to allow Medicare to benefit from lower negotiated prices after all drugs, regardless of molecule size, have been on the market for 13 years.

Patients need more new treatments, both small and large molecules. But scientists should pursue these therapies based on their medical potential, not because the government has arbitrarily incentivized one over the other.

Rosa Mendoza is the founder, president, and CEO of ALLvanza, a nonprofit organization that advocates for the success of Latinos and other underserved communities in our innovation and technology-based society.