Mariana Sanchez

BBC News Brazil in Washington

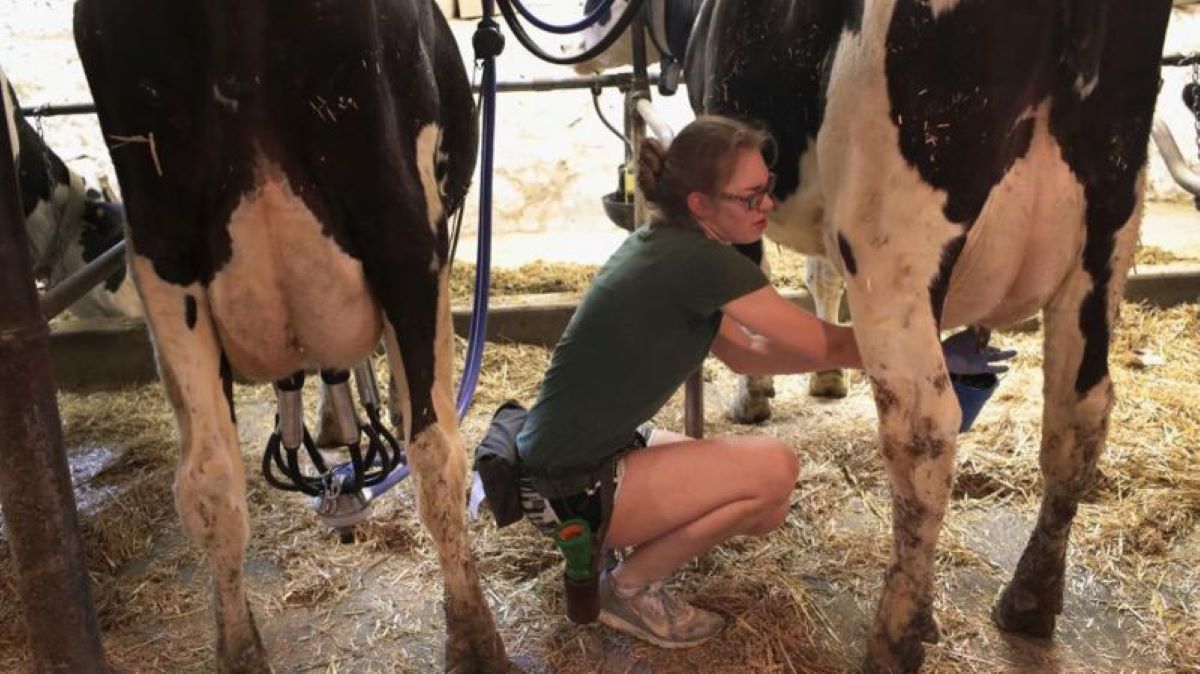

In the richest country in the world, child labor is becoming a more frequent reality, and not always against the law.

The United States is facing a wave of exploitative child labor: In 2022, federal inspectors found nearly 4,000 children working illegally.

It is the maximum recorded in the historical series of the Labor Department, available since 2013, when the inspection found 1,400 minors in this situation.

But that is not all. A poll released in May by the Economic Policy Institute, a left-wing think tank, showed that in the past two years, at least 14 of the 50 US states have discussed – and eight have passed – local laws that reduce barriers to child labor exploitation.

The bills authorize, for example, the employment of 14-year-old children in 6-hour night shifts and heavy work.

16-year-olds may be admitted to risky or physically demanding activities, such as demolitions or slaughterhouses, or even serve alcohol in bars (although it is illegal to drink before the age of 21 in the country). Some of the bills also provide for them to be paid half as much as adults.

Each of the 50 states can legislate on the subject, but federal regulations state that young people between the ages of 14 and 15 can work a maximum of 3 hours a day during the school period, never after 7:00 p.m., and prohibit activities in sectors such as construction or the food industry, considered “oppressive to children” by US law.

Adolescents of 16 or 17 years old cannot work with explosives, mining and road works, among others.

One of the leading American experts on child labor calls this trend in the United States “striking.”

“I never thought that after more than 30 years working in [el tema del] child labor in much poorer countries, (…) my focus would suddenly turn to the US,” economist Eric Edmonds, a professor at Dartmouth College, told BBC Brazil.

Iowa recently passed child labor standards that contravene the Fair Labor Standards Act, which in 1938 outlawed the exploitation of minors nationwide.

“The approved law allows adolescents to work in the manufacture and storage of fireworks. Does anyone really want 16 year olds making explosives? It’s crazy,” says Reid Maki, coordinator of the Child Labor Coalition, an organization that has studied the issue for decades.

In the US, the idea that children should be able to earn and manage resources from an early age is popular. It is expressed in cultural icons like the cartoon Snoopy, in which the character Lucy has her lemonade stand, or in typical high school movies.

“We all agree that work can be useful and that it teaches teens responsibility and skills, but it should be limited in hours and restricted to safe jobs,” Reid says.

“What we are seeing with the easing [de las leyes] at the state level is that in Minnesota, for example, they want children to work in construction, which is not safe, ”he adds.

“It is not a 19th century problem”

What the US is experiencing, however, is something very different from that image of teenagers who earn a few dollars delivering a newspaper in the neighborhood or mowing the neighbor’s lawn.

Nobody knows the real magnitude of the problem, since there are no official statistics on minors employed in the country.

“In the early 1970s, the US stopped collecting data on employment of children under 16 based on the assumption that there were simply no children under 16 working in the country,” says Edmonds.

The instrument to measure the problem is the inspections of the federal government, and experts agree that the statistics point to a growing problem.

After reporting a 69% increase in child labor incidents last year compared to 2018, the US Department of Labor announced in late February that it already had at least 600 investigations open in 2023 alone.

“This is not a 19th century problem, this is a problem of today,” then-Labor Secretary Marty Walsh said in a February 27 statement.

The upward trend in child labor in the US is explained by a set of factors that have put pressure on socially and economically vulnerable children to take jobs that most adults do not want.

The North American country registers full employment in 2023. The unemployment rate in May was 3.7%, slightly higher than that of April, which was the lowest in five decades.

Most job openings take three months or more to fill, precisely because of a lack of candidates, according to the Center for Economic and Business Research.

Minor immigrants who cross the border alone

The labor shortage is explained, at least in part, by one of the most divisive issues: immigration.

Former President Donald Trump has cracked down on the flow of immigrants, who with little change remain in the Joe Biden government.

In practice, the only demographic group that is not subject to immediate removal if they cross the border without permission are unaccompanied minors.

As a result, the number of immigrants as young as 17 crossing over to the US side has skyrocketed. In 2021, the authorities registered almost 139,000; in 2022, 128,000.

Child migration lawyers assured BBC Brazil that, in fact, the US government does not know what happens to these children once they are handed over to a guardian.

“We know that these children are often relocated to poor families, with several children, with economic difficulties, without documentation,” said one of these lawyers.

The Department of Health and Human Services did not respond to BBC inquiries on this matter.

For specialists interviewed by BBC Brazil, these children have become obvious targets for some industries.

“Although it is true that there is a growing demand for labor, this factor alone explains the increase in child labor. What is causing the increase is corporate greed, backed by lobbyists and politicians, and the willingness to exploit vulnerable populations to obtain employees at the lowest possible cost,” says Chavi Keeney Nana, a professor at the University of Michigan Law School. with experience working with multinational corporations and financial institutions.

Nana argues that there is no mere coincidence between the huge increase in unaccompanied minors at the border and the increase in child labor exploitation.

“Industries involved often include local or national restaurant associations, hospitality industry groups, and in some cases construction. There is also lobbying by the National Federation of Independent Companies (NFIB) on behalf of various sectors”, says researcher Jennifer Scherer, author of the study from the Economic Policy Institute, to BBC Brazil.

“And clearly there is also a role being played by a right-wing think tank called the Foundation for Government Accountability (FGA), which has coordinated lobbying in some states and is speeding passage of some of the bills,” he adds.

The BBC contacted the NFIB and the FGA but received no response.

The arguments in favor of child labor

On its website, the FGA argues that “there are many advantages for adolescent workers entering the job market at this time, but unnecessary bureaucratic oversight could delay or prevent them from seeking these opportunities.”

Among the “unnecessary bureaucracies”, he points out against school permits for the employment of students and external evaluations of the conditions of job security or health of adolescents to perform certain functions.

Some states have already abolished such restrictions.

“The worker crisis has crippled the US economy and supply chains. With 6.3 million people unemployed and almost 11 million jobs available, there are job offers in all sectors (…) While millions of adults prefer to stay at home instead of working, adolescents across the country are incorporating into the labor force”, affirms the FGA.

“Teenagers want to work. Let’s leave them”, concludes the study center, which is in favor of restricting social programs and praises the states with a Republican majority while criticizing the Democratic management.

This position is criticized by defenders of children’s rights.

“Companies have identified a job offer that could be more easily exploited: they are children in a foreign country without guardians or means of subsistence (in many cases). They saw an opportunity to save on labor costs and they jumped at it,” says Nana of the University of Michigan.

“They understood that this often results in fines and built these costs into their business model. The savings they achieved by hiring vulnerable workers with little chance of claiming any rights outweighed the fines,” he notes.

“Given the growing evidence of child labor, what several states have done is pass laws that facilitate the employment of children and do not protect them,” concludes the expert.

Low productivity and commitment to the future

For Edmonds of Dartmouth College, the argument that children and adolescents will save the economy is based on false premises.

“Kids are terrible workers, very unproductive, easily distracted. Adolescents are more interested in many other things instead of working hard,” says the economist, citing skepticism that minors would solve the country’s labor shortage.

“I can’t believe these state legislators want their own children to work all night to solve the labor shortage. Even more so when the problem can be easily fixed with a little more immigration, ”he goes on to say.

“For me, the issue of child labor is one more facet of our culture war.”

In the world, 160 million children -1 in 10- work, according to Unicef figures from the beginning of 2020, the latest data available.

The vast majority are from socially and economically vulnerable families.

The most obvious consequence is school absenteeism, which affects one in three. Without completing their schooling, these children see their future compromised, says UNICEF, since in adulthood it is difficult for them to find better paid jobs, in a cycle of repetition of poverty.

Studies also suggest that child labor can cause physical and mental harm to exposed children.

For Scherer, what some US states are doing now is, in part, repeating history.

“USA. it was built on various forms of child labor, from the work of enslaved children to the industrial revolution, when children from poor families worked in our first textile factories and mines”, recalls the researcher.

And he closes with a reflection: “This is not the first time that industry groups have taken an interest in blocking child labor regulations. This is just its latest version.”

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC News World. Download the latest version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.

- Do you already know our YouTube channel? Subscribe!

See original article on BBC